Why Do Women Respond Differently Than Men to Depression Treatments?

The researchers believe that the answer lies in the brain.

Researchers have identified a possible explanation why women may not react to treatments for depression similarly to men.

Despite the fact that there are treatments for depression, many people find these treatments to be unhelpful at times. Furthermore, women have greater rates of depression than males, but the reason for this disparity is unclear, making their illnesses sometimes more complicated to treat.

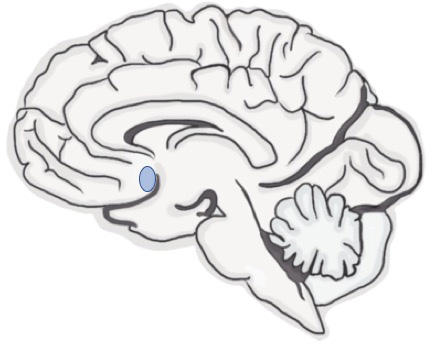

Researchers from the University of California, Davis collaborated with researchers from Mount Sinai Hospital, Princeton University, and Laval University, Quebec, in an attempt to understand how the nucleus accumbens, a particular region of the brain, is impacted during depression.

The nucleus accumbens plays a crucial role in motivation, how we react to pleasurable events, and how we connect with others—all of which are impacted by depression.

Previous studies of the nucleus accumbens revealed that specific genes were switched on or off in women with depression but not in males.

Depression symptoms may have been triggered by these alterations, or the depressive episode itself may have altered the brain.

The researchers examined mice that had been exposed to unfavorable social interactions, which are more likely to cause depression-related behavior in females than males.

This allowed the researchers to differentiate between these two hypotheses.

The nucleus accumbens (represented in blue) is a part of the brain that controls motivation.

Researchers from UC Davis compared samples of the nucleus accumbens in mice and humans to find clues to how this part of the brain is affected by stress and depression in males and females.

“These high-throughput analyses are very informative for understanding long-lasting effects of stress on the brain.

In our rodent model, negative social interactions changed gene expression patterns in female mice that mirrored patterns observed in women with depression,” said Alexia Williams, a doctoral researcher and recent UC Davis graduate who designed and led these studies.

“This is exciting because women are understudied in this field, and this finding allowed me to focus my attention on the relevance of these data for women’s health.”

The study was recently published in the journal Biological Psychiatry.

After identifying similar molecular changes in the brains of mice and humans, researchers chose one gene, regulator of g protein signaling-2, or Rgs2, to manipulate.

This gene controls the expression of a protein that regulates neurotransmitter receptors that are targeted by antidepressant medications such as Prozac and Zoloft.

“In humans, less stable versions of the Rgs2 protein are associated with increased risk of depression, so we were curious to see whether increasing Rgs2 in the nucleus accumbens could reduce depression-related behaviors,” said Brian Trainor, UC Davis professor of psychology and senior author on the study.

He is also an affiliated faculty member with the Center for Neuroscience and directs the Behavioral Neuroendocrinology Lab at UC Davis.

When the researchers experimentally increased Rgs2 protein in the nucleus accumbens of the mice, they effectively reversed the effects of stress on these female mice, noting that social approach and preferences for preferred foods increased to levels observed in females that did not experience any stress.

“These results highlight a molecular mechanism contributing to the lack of motivation often observed in depressed patients.

Reduced function of proteins like Rgs2 may contribute to symptoms that are difficult to treat in those struggling with mental illnesses,” Williams said.

Findings from basic science studies such as this one may guide the development of pharmacotherapies to effectively treat individuals suffering from depression, the researchers said.

“Our hope is that by doing studies such as these, which focus on elucidating mechanisms of specific symptoms of complex mental illnesses, we will bring science one step closer to developing new treatments for those in need,” said Williams.